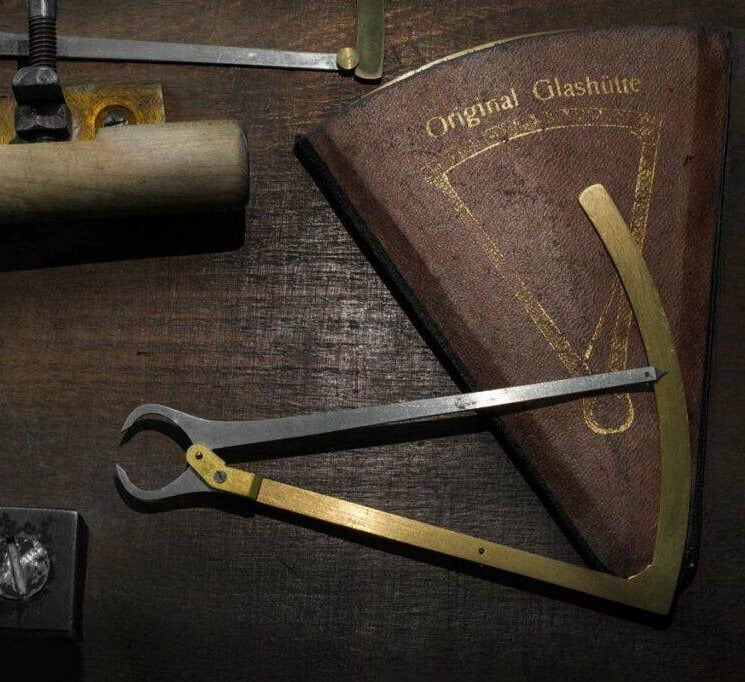

1845

The German Watchmaking School Glashütte

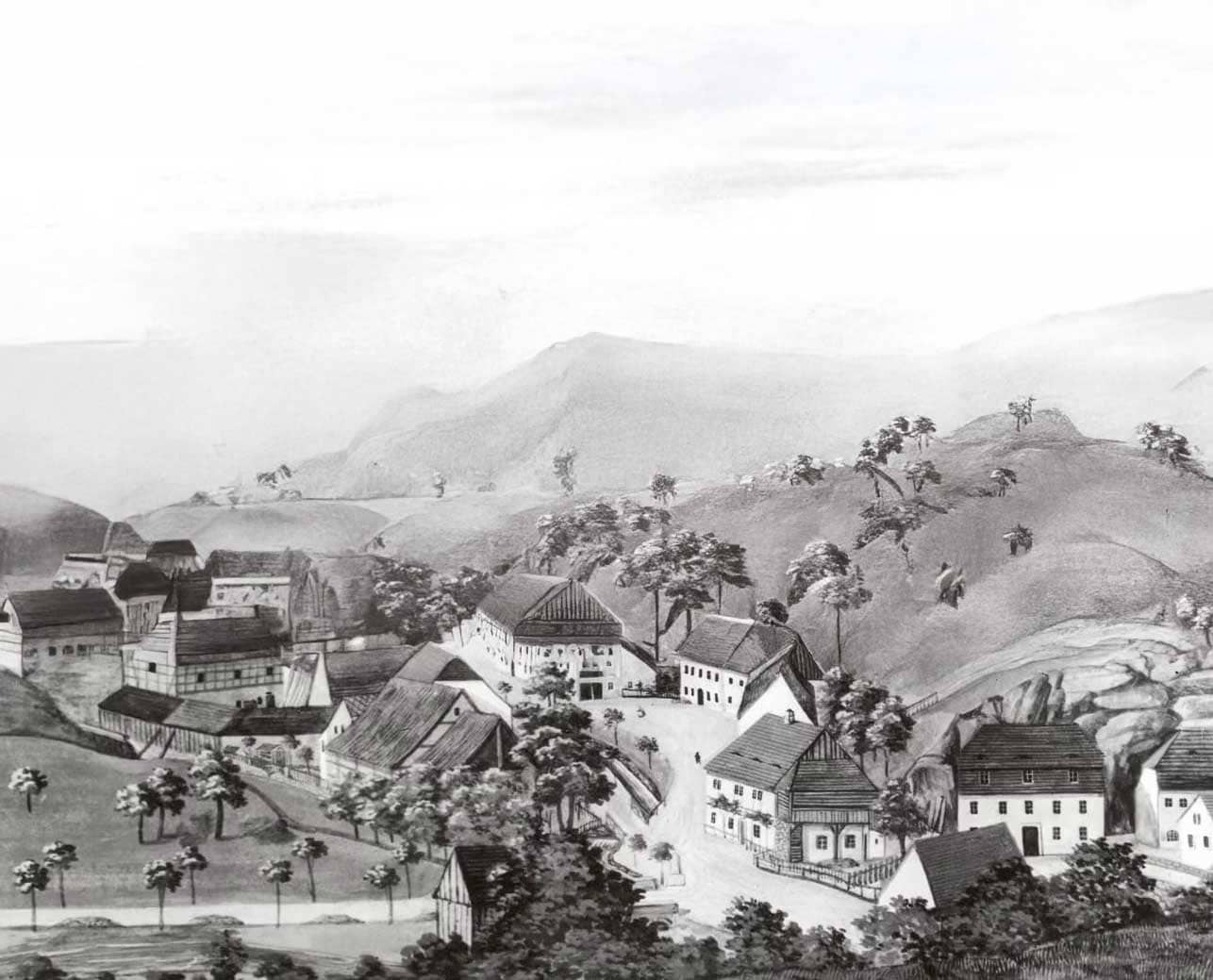

When the first watchmakers settled in Glashütte in the middle of the 19th century, the journey to Dresden, 30 kilometres away, took around three days. The remote region in the Ore Mountains had previously lived from mining for centuries. But as ore deposits dwindled, the local population feared for their livelihood.

The fact that the art of watchmaking gained a foothold in Glashütte, of all places, was no coincidence. It was a well-planned project supported by the Kingdom of Saxony to give the region a new perspective. However, the government did not provide funding for the construction of factories, but solely for the training of watchmakers – thus laying the foundation for an industry that was to focus on specialised expertise and its transfer from the outset.

In just a few years, Glashütte managed to rise from a humble mining town to an international institution in the manufacturing of high-precision watches. This was not the work of a single individual or even of a single company. It was a joint effort by great visionaries who supported each other and maintained close friendships. Their greatest legacy, however, was to be the German Watchmaking School Glashütte.

1878

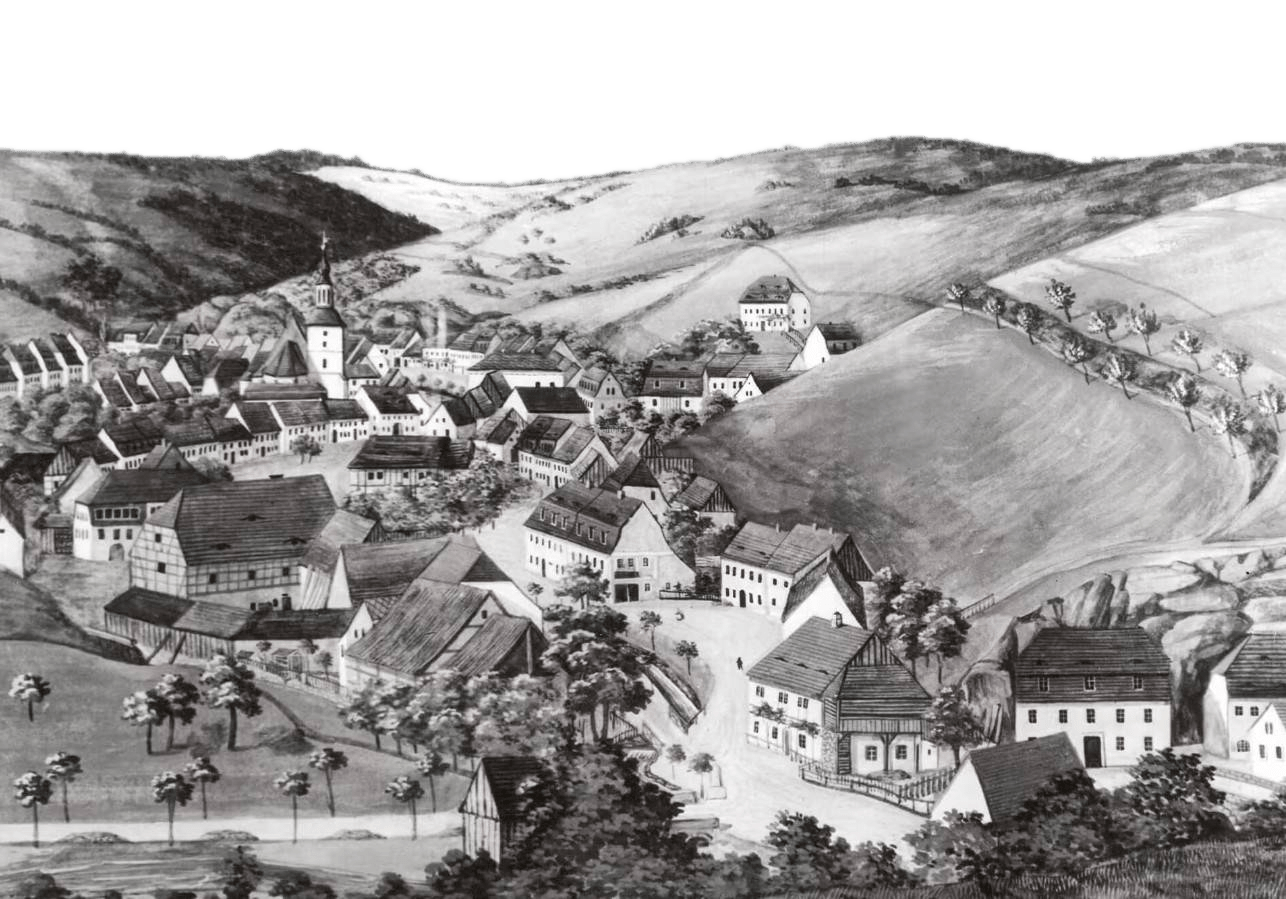

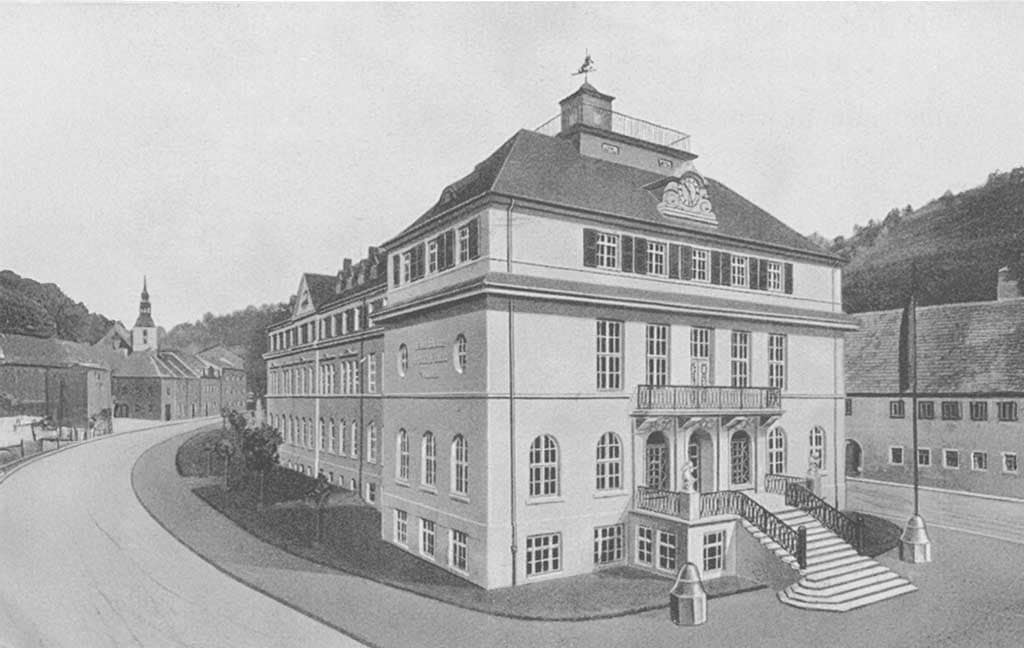

The opening ceremony took place on May 1, 1878. The first 23 students were taught in two rooms of the Glashütte community school building. However, just one year later, more people wanted to learn the watchmaking craft at the school than the premises would allow. A separate school building was therefore built in the centre of Glashütte, which was completed in 1881 and had a capacity for 60 to 80 students. After some time, even these premises were no longer sufficient. The building was therefore extended in 1921 and was also given its own park with a monumental fountain.

Admittance to the German Watchmaking School Glashütte was a great honour, and there was a strong sense of community among the students. They formed fraternities in which they spent their free time and supported other students far beyond their own apprenticeships. The graduates spread the ethos of Glashütte watchmaking throughout the world and wore the title ‘Graduate of the German Watchmaking School Glashütte’ with pride for the rest of their lives.

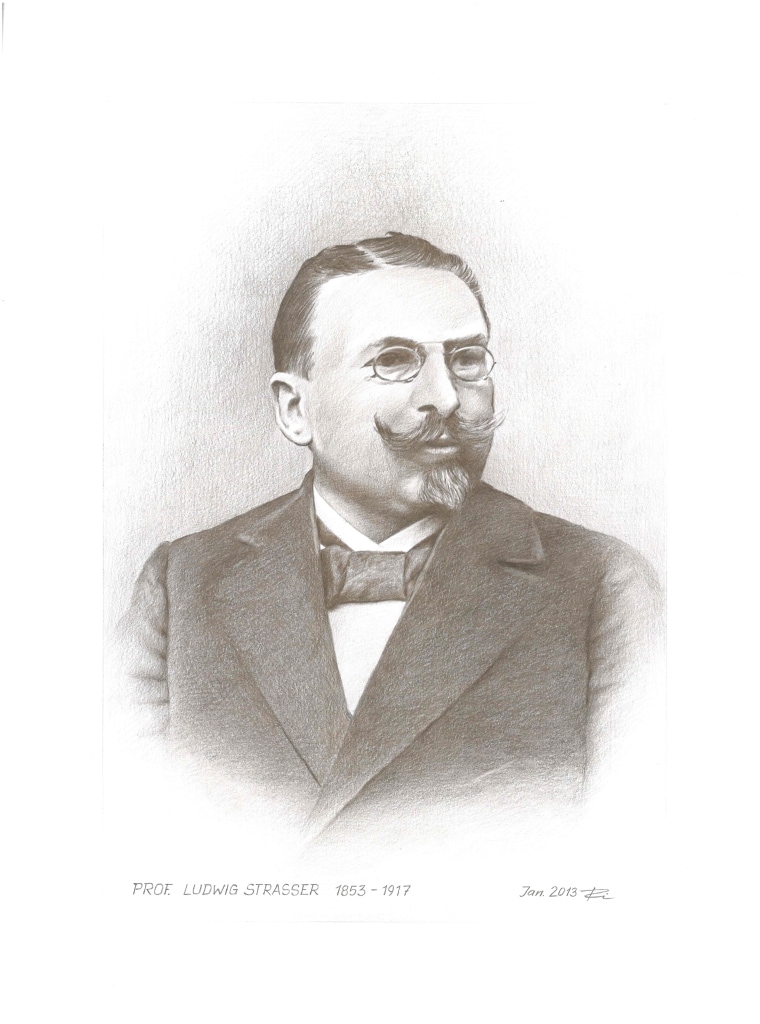

Similarly, for many master watchmakers and successful industrialists from Glashütte, to be named a teacher at the renowned school was an honour as prized as a knighthood. The watch manufacturer Ludwig Strasser, famous for his precision pendulum clocks and the invention of the free spring detent escapement, played a key role in shaping the institution since its foundation. Initially, he wanted to remain part of the Strasser & Rohde company. However, when the workload of his role as managing director became too heavy alongside his teaching activities, he decided in favour of the school. In 1885, he took over the position of director, which he would hold for 32 years.

1920

Not only did the German Watchmaking School Glashütte pursue the goal of training skilled watchmakers, it also aimed to promote innovation. In the early 20th century, Alfred Helwig, master watchmaker and teacher at the school, took up the challenge of further developing the most elaborate complication in the art of watchmaking: the tourbillon. He involved his students in the work right from the start. Together, they succeeded in 1920 in mounting the construction on one side only – for the first time – thus freeing it from the upper part of its cage. The so-called Flying Tourbillon went on to become one of Glashütte's most famous inventions.

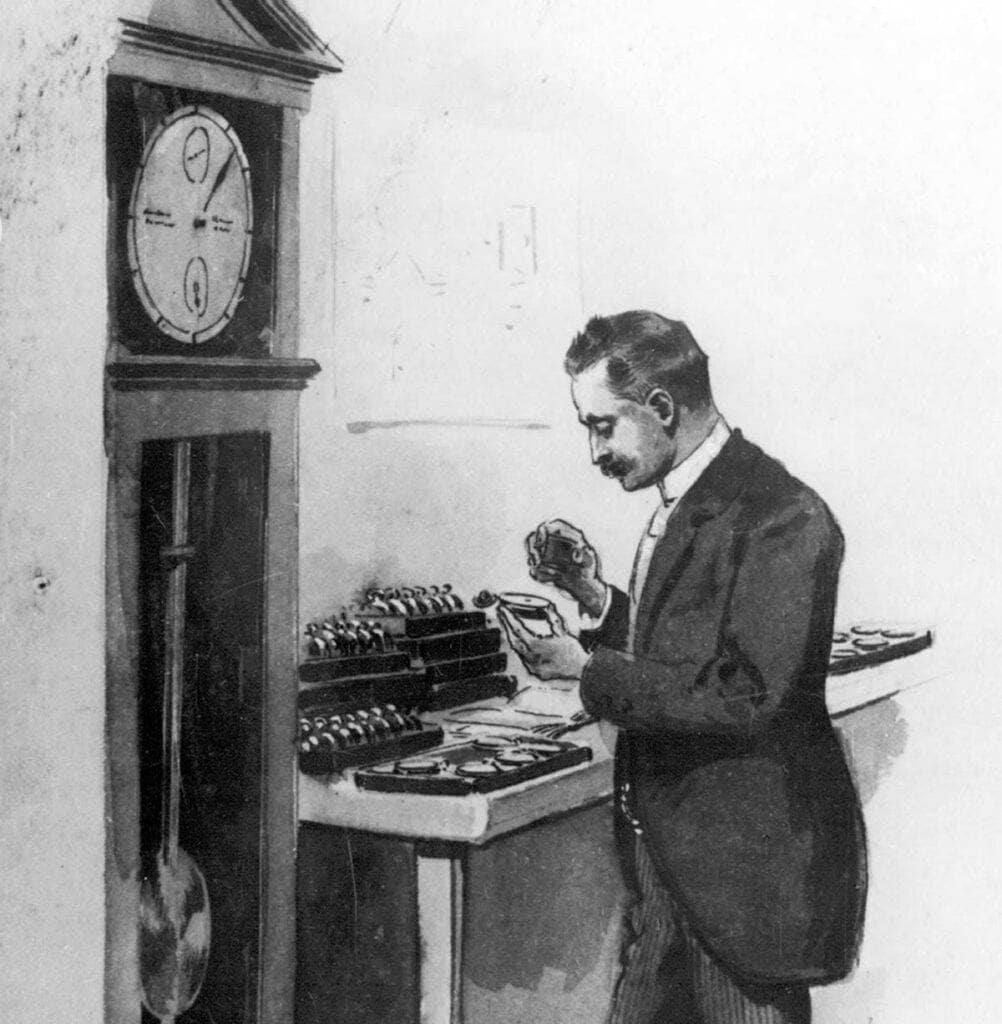

Every Saturday, the school building became the venue for a special ritual. From 8:00 a.m. to 8:10 a.m., the Berlin observatory transmitted a time signal to Glashütte via one of the first Morse Code lines in the Ore Mountains. With the help of a so-called coincidence clock, the time could be checked to the nearest tenth of a second. In his writings, Alfred Helwig described the event in vivid terms: ‘This taking of the time signal was an almost ceremonial act, accompanied by the greatest silence in the whole building, so that the coincidence of the beats could be heard very clearly. The headmaster and teacher were present, and each time a few students were called in so that they could all gradually familiarise themselves with the time signal reception.’

For many decades, the German Watchmaking School formed the social core of the Glashütte watch industry. In 1951, the community of independent companies became a state-owned group, VEB Glashütter Uhrenbetriebe. After German reunification, Glashütter Uhrenbetrieb GmbH became the legal successor to the former state-owned group and thus became the sole heir to the historic watch industry of its hometown. Today, it unites the legacy dating back to 1845 under the brand Glashütte Original.

Among the many aspects of this legacy is the fact that the company’s young talents are still trained in the same building as they were in 1881. Since 2002, Glashütte Original’s own watchmaking school has borne the name of Grand Master Alfred Helwig. With their ideas and drive, the young watchmakers, toolmakers and machinists who graduate here year after year ensure the future of Glashütte craftsmanship.

Glashütte Original has always remained true to the ideals of its forefathers. With the same innovative strength on which its success was once founded, the manufactory continues to strive for absolute perfection. Behind the scenes, the company’s engineers and watchmakers continue the work of great masterminds such as Alfred Helwig. With the patented Flyback Tourbillon, they succeeded in further developing Helwig’s ingenious mechanism. A vertical clutch brings the centrepiece of the Senator Chronometer Tourbillon to a standstill when the crown is pulled. If the crown is pulled to the next position and held there, the tourbillon cage rotates gently back to the zero mark of the second hand at its tip. Pressing the crown sets the whirlwind effortlessly in motion again – a masterful technical achievement that the Grand Master himself would doubtless have been quick to acknowledge.